Populism behind the Great Firewall of China

Ako Tomoko (Japan)

Associate Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo / ALFP Advisory Committee Member

Populism is spreading across the globe: just some examples are the United Kingdom’s decision to withdraw from the European Union (“Brexit”), Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential election, and intensifying anti-Japanese, anti-Chinese, and anti-Korean attitudes in Asia. One might assume populism to be a phenomenon unique to democratic nations, a strain of thought absent in countries like China, but populist stirrings are now emerging even there.

Populism is a political style through which politicians seek to transcend fixed, traditional support bases and appeal to a wider public (“the people”). Political scientist Mizushima Jiro characterizes the movement as a “critique of established politics and the prevailing elite from the standpoint of the people.”1 Populists aim to give the general public a voice in opposition to the established political structure and elite classes—a reformist perspective with deep roots in the people’s mistrust of democratic institutions that ostensibly fail to reflect their will.

Who are “the people” then? Quoting Margaret Canovan, Mizushima outlines three classifications of what “the people” represents:2 (1) ordinary people (the “silent majority” whom the privileged have largely ignored), (2) united people (the people of a country, not the specific organizations and factions that divide it, who share in a single, common will); and (3) our people (a homogenous grouping of similar individuals who identify themselves as citizens or members of an ethnic group, often distinguishing itself from outsiders including foreigners, people of different ethnicities, and religious minorities).

In China, the Constitution defines “the people” as “workers and peasants.” As a “people’s democratic dictatorship,” according to Article 1 of the document, China positions workers and peasants as a ruling, dictatorial class that plays the central role in opposition to the capitalist class. However, the Constitution also defines the Communist Party as the embodiment of the Three Represents: the development trend of China’s advanced productive forces, the orientation of its advanced culture, and the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the Chinese people.

In doing so, the document effectively opens the Communist Party to private-sector entrepreneurs—the representation of “advanced productive forces.” The Chinese Constitution thus presents a contradiction, simultaneously claiming itself to be a “people’s state” where workers and peasants represent the masters of society but also admitting the would-be capitalist enemies of the “people” into the fold.

The term zhonghuaminzu (the Chinese nation or the Chinese ethnicities) is another key driver behind the Chinese conception of the “people.” Emphasizing the notion that “the Chinese dream is the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” leaders stress a vision of comprehensive unity among all the segments of the zhonghuaminzu (ethnic minorities, Hong Kongers, and Taiwanese included) in unbending opposition to the hostile foreign forces threatening the solidarity of the multi-ethnic Chinese state.

In reality, however, Chinese nationalism is relatively weak. The rhetoric’s emphasis on banding together against “hostile foreign forces” betrays a weakness in the nation’s overall solidarity in and of itself, revealing the country’s trepidations about the influx of foreign capital and ideologies. The government often claims that ethnic minority issues undermine Chinese solidarity, as well. While the country points to outside capital and concerns about minorities as hurdles to unification, the biggest threat to zhonghuaminzu unity is the fragmentary, segmented structure of the Han race. The rich-poor gap is a gulf of disparity—and that class stratification is essentially inborn, as one’s household register largely defines one’s standing. Systems for university entrance examinations and social security vary from region to region, as well, with people in major urban centers at a distinct advantage over their rural counterparts. Reconciling the interests of the divergent social strata in China is by no means a simple task.

Chinese Politics and Populism in the Internet Era

The late 1990s and early 2000s represented a golden age for social media in China. For people who had long lacked a full voice in political discourse, the internet provided a powerful platform for discussions of virtually any topic, a medium for collaborative learning, and, in many ways, a catalyst for transformative enlightenment and solidarity. As flaming and fake news have shown, though, the internet’s unprecedented freedom of speech can engender negative consequences. A Chinese proverb says that ‘no disturbance leads to no solution, a small disturbance leads to a small solution, and a big disturbance leads to a big solution’—and that mindset has taken on a new resonance. Netizens can now harness online resources to ignite popular uproar about issues from the legal domain, making it easier to fuel bigger disturbances into outcomes that are more favorable to them.

Clashes between grassroots social media and state-run media are heating up, too. Although social media helped the Weiquan movement, an activist effort to defend civil rights, gain traction in the early 2000s, recent years have seen the government suppress spikes in online civil rights-related activity by framing the dialogue as turbulence that jeopardizes social stability.

There have also been cases where popular sentiment on internet platforms has swayed judicial decisions—even death sentences. As local governments wield authority over court personnel affairs and budgetary matters, people in positions of power on a local scale tend to enjoy favorable judicial treatment. In that type of society, opinion in social media can play a role in defending and supporting vulnerable groups. However, some harbor reservations about the fact that official court decisions can come down to which side proves itself more strident online.

Since Xi Jinping came to power, media censorship and efforts to manipulate popular sentiment have become more prevalent. Tighter restrictions on press, media, and academic freedom have given lawyers, activists, and scholars challenging conditions to work under, but stricter controls actually seem to reflect an increasingly wary stance on social media.

Ren Zhiqiang, an outspoken “Big V” opinion leader (an individual with large numbers of followers on social media) in the real estate field saw his account closed after sounding off on social issues, for example. A university researcher lost his job for “having non-mainstream values” after posting criticism of China’s history education policies online.

The Global Decline of Liberal Democracy and the Rise of Populism in China

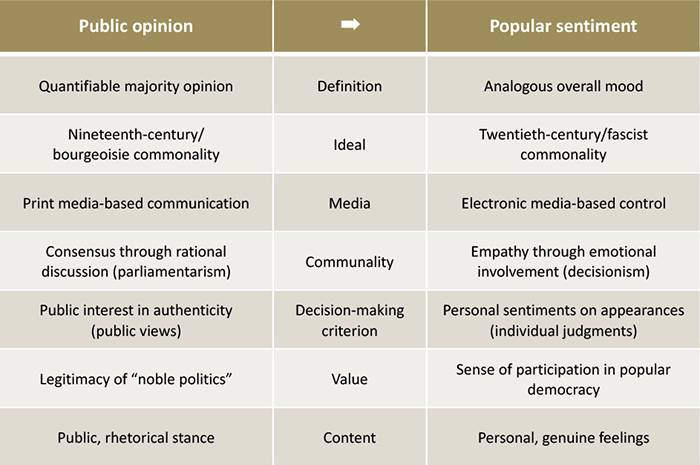

Sato Takumi differentiates “public opinion” and “popular sentiment” along seven lines.

Public opinion forms via the maturation of personal opinions into public perceptions; reaching a consensus through rational discussion is one example of public opinion formation. On the other side is popular sentiment, which can both embody positive elements—participation in popular democracy and genuine feelings, for instance—and reflect fascist tendencies.

In a country where citizens have a limited voice in national politics, the advent of the internet age brought about a boom in popular sentiment in early 2000s China. The government, apprehensive about the potential perils of open online discourse, has taken steps to contain that popular sentiment. However, one cannot expect China to have a foundation for rational discussion in place of popular sentiments, either, as the sizable gap separating class strata and the minority issues affecting the Chinese people make inter-class communication quite the challenge.

That concern applies to more than just China: the same types of issues might also be affecting immigrants and other segments of the population in Japan, Europe, and the United States. The patterns of populism, where barriers to inter-class communication result in groups seeing each other as enemies, could manifest themselves in virtually any country.

Populism also has ties to propaganda, given its ability to bring people into the political realm. Hitler, focusing specifically on appealing to the working classes, formed the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the Nazi party) in the hope of reintegrating workers into the national body and co-opted the red flags and fiery oratory styles of the social democracy movement to stir up support.

According to Satō, Hitler’s mode of democracy centered on mobilizing workers—who had long been exiles from the world of print-driven education—and making the working classes feel that they were pivotal players in the thick of political discourse. The conditions in modern-day China pale in comparison to those in Hitler’s Germany, of course, but I think we need to be aware of the potential for crisis: if populist upswells go too far, any country—be it China, the United States under Donald Trump, or even Japan—could very well find itself in a situation that all too closely resembles the Nazi regime.

Satō underscores the importance of public opinion in overcoming fragmented class structures and moral systems. However, in countries like China with large populations of low-income earners lacking opportunities to gain knowledge and information, the process of forming public opinion can be rife with roadblocks. Dealing with popular sentiment thus takes precedence over consolidating public opinion.

The Chinese government is currently implementing measures to clamp down on lawyers, silence activists, and delete content on social media in order to keep demonstrations to a minimum, all in the name of “social stability.” In the short term, those initiatives might certainly appear to be effective stabilizers—but is smothering adverse discourse a legitimate approach to ensure sustainable development? We need to address these issues from a long-term perspective.

The contents of this article reflect solely the opinions of the author.